This blog is the second part of a planned series on Illinois’ public pension systems. The first was on the Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund (CTPF). This post focuses on the four pension funds that the City of Chicago is responsible for: the Municipal Employees’ Annuity and Benefit Fund (MEABF), the Laborers’ and Retirement Board Employees’ Annuity and Benefit Fund (LABF), the Policemen’s Annuity and Benefit Fund (PABF), and the Firemen’s Annuity and Benefit Fund (FABF).

Combined, Chicago’s four pension funds are only 23.80% funded. The funding level is the ratio of assets (think money in the bank) to liabilities (value of retirement benefits). Any funding level below 100% is underfunded. Illinois’ and Chicago’s pension systems are (in)famous for their poor funding. The table below shows each of the funds’ current funding levels and the number of current employees in each system.

| Pension Fund | Current Funding Level (as of 12/31/2021) | # Current Employees |

| MEABF | 21.95% | 32,925 |

| LABF | 44.50% | 2,602 |

| PABF | 23.98% | 12,126 |

| FABF | 20.13% | 4,735 |

A pension system is fully funded if its funding level is 100%, and Chicago’s pension funds are all far from full funding. Being “fully funded” means there are no unfunded liabilities. Think of unfunded liabilities as a form of debt that the City has to pay off.

Combined, Chicago’s four pension funds unfunded liabilities totaled $33 billion at the end of 2021, and the City of Chicago has to pay off 90% of that debt by 2055 (for PABF and FABF) and 2058 (for MEABF and LABF). An important caveat is that unfunded liabilities are not a fixed form of debt. Instead, unfunded liabilities are in constant flux and change as assets and liabilities change. If the pension funds, for example, suffer massive investment losses (as happened during the Great Recession) their assets decline, and unfunded liabilities in-turn increase. So the unfunded liabilities will change from year-to-year. Even as unfunded liabilities change, the pension funds still must be 90% funded by 2055 and 2058.

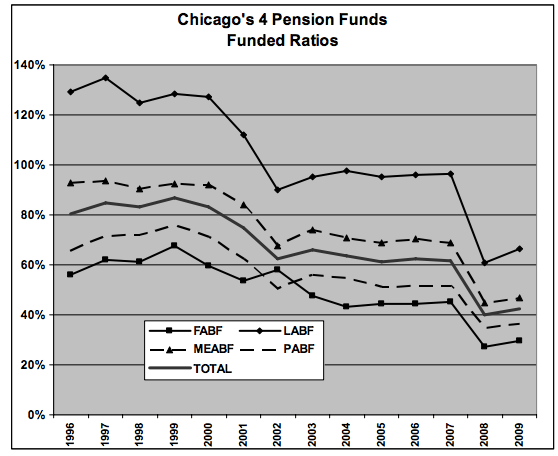

While Chicago’s pension funds have low funding levels today, all four were better funded in the late 1990s. In fact, the LABF’s funding level exceeded 100% until the early 2000s. Like the CTPF, Chicago’s pension funds have seen their funding levels decline over time. The chart below shows the four pension funds’ funding levels between 1996 and 2009 (Source: Commission to Strengthen Chicago’s Pension Funds Final Report, p. 18)

As the chart above shows, all four pension funds saw their funding levels erode between 1996 and 2009. The MEABF and LABF went from being well-funded to poorly funded, while the PABF and LABF were always underfunded. So what happened?

In 2008, Mayor Daley put a commission together to answer that very question, and the commission issued its final report on April 30, 2010. I highly recommend reading the report. The final report summarizes what happened in the following paragraph:

In a nutshell, for all four pension funds inadequate City contributions was a key reason. For MEABF and LABF another key factor was that in 1998 benefits were increased while the City’s required contributions were actually cut. In other words, the benefits for MEABF and LABF were enhanced without also putting in place a way to pay for those benefits.

The remainder of this post focuses on the history of the City’s required contributions. As a caveat, while I focus on the history of the City’s contributions, insufficient contributions is not the sole reason why the pension funds are underfunded today.

A Dive Into Chicago’s Required Pension Contributions

Before diving in, a key thing to know is that Chicago’s pension funds are governed by state law. There are separate articles for each of the pension funds within the Illinois Pension Code. What the City has to pay into the pension funds is dictated by state law, so making changes requires action by the Illinois General Assembly and Governor. Changing the funding plan–which determines the City’s contributions–is NOT something the Mayor and City Council can do unilaterally (Mayor Emanuel argued the City couldn’t put more money into the funds than was required by state law; however, Mayor Lightfoot did just that for 2023 and Cook County has been doing it for years).

A pension system’s assets come from three sources: employee contributions, employer contributions, and investment returns. Typically, employee contributions are fixed rates of pay. In contrast, employer contributions are a variable amount that is based on the employer’s share of the normal cost (this is the cost of benefits being earned) and a funding plan to pay down any unfunded liabilities.

So the way it should work is that an employer’s contributions increase as unfunded liabilities increase. This has not been the case for Chicago for many decades. Moreover, the City’s contributions weren’t even connected to the cost of benefits being earned each year by active employees. Instead, the City’s contributions were fixed multipliers of employees’ contributions. For example, for every $1 a municipal employee put into the MEABF the City contributed $1.25. The table below shows the multipliers and when they were last set.

| Pension Fund | City Multiplier | Year Multiplier Took Effect | Note |

| MEABF | 1.25 | 1999 | Multiplier was 1.69 from 1978-1999 |

| LABF | 1 | 1999 | Multiplier was 1.37 from 1978-1999 |

| PABF | 2 | 1982 | Multiplier was 1.97 from 1975-1981 |

| FABF | 2.26 | 1982 |

I cannot stress enough how bad a set up this was. This meant that for decades the City’s contributions into the pension funds were divorced from the cost of benefits and de-linked from the pension funds’ finances. The City’s contributions being fixed multipliers of employee contributions was also an unusual set-up.

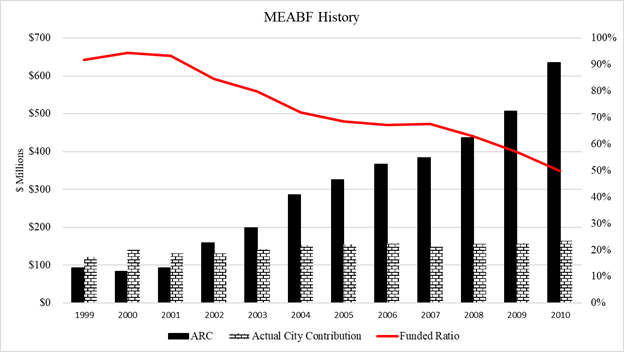

The City’s actual contributions can be compared to the actuarial “annual required contribution” (ARC). The ARC is what the contributions should have been if they were tied to benefit costs and the funding levels. The figure below compares the ARCs and actual City payments for the MEABF between 1999 and 2010 (the bars), and also includes the funding level (the red line).

As the chart shows, when the MEABF was well funded (years 1999, 2000, and 2001) the City’s actual contributions exceeded the ARC. But once the funding level started decreasing the ARC increased, but the City’s contributions basically stayed flat. Because the City’s contributions were fixed multipliers, as unfunded liabilities grew (and the funding level deteriorated) there was no way to pay it down, so the problem snowballed. The problem also become two-fold: 1) the rapidly deteriorating funding level of the pension funds and growing risk of insolvency; 2) the widening gap between what the City should have been putting into the pension funds and its actual payments.

Cut to the 2010s….By that time the situation was so dire that the pension funds were projecting they would all run out of money in the coming decades. In 2012, the LABF projected it would be insolvent by 2027 and the MEABF projected it would be insolvent by 2025. If the pension funds ran out of money this would mean there wasn’t money to pay out retirees benefits. At the time, Mayor Emanuel argued the City wouldn’t be on the hook for paying the benefits if that happened. The looming insolvency of the pension funds also contributed to downgrades of the City’s credit ratings. I’m not going to revisit all of the politics around pensions from that time, but a main thing to know is that Mayor Emanuel had to lobby Springfield for changes and put forth several proposals. This also meant that there were many years between when Daley’s pension commission issued its final report and when changes were actually made.

After other proposals failed (one of which was signed into law, but subsequently struck down by the Illinois Supreme Court), the funding laws for Chicago’s four pension funds were finally changed by Public Act 99-506 (for FABF and PABF) and Public Act 100-23 (for MEABF and LABF).

Rather than simply starting to properly fund the pension systems right away though, there were five-year “ramps” put in place. Basically, the City’s contributions for 2015-2019 for FABF and PABF and 2017-2021 for LABF and MEABF were fixed dollar amounts, and those fixed dollar amounts were written into state statute. Below is the text for the ramp period for the PABF from state statute.

Because the payments during the ramp periods were fixed dollar amounts this meant that for those years the City’s payments into the pension funds were still not tied to benefits being earned or unfunded liabilities. In the long run these ramps cost the City a lot of money.

The table below summarizes the funding plan provisions from Public Acts 99-506 and 100-23, and includes the funding target year for each fund, dedicated revenue sources, and the ramp periods.

| Fire Fund | Police Fund | LABF | MEABF | |

| Ramp Period | Property tax levy years 2015-2019 | Property tax levy years 2015-2019 | Property tax levy years 2017-2021 | Property tax levy years 2017-2021 |

| Dedicated revenue source/note | Property tax increases; casino revenue | Property tax increases; casino revenue | 911 surcharge | Water-sewer usage tax |

| Fund Law After Ramp | City contributions must be sufficient so fund is 90% funded by end of FY2055 | City contributions must be sufficient so fund is 90% funded by end of FY2055 | City contributions must be sufficient so fund is 90% funded by end of FY2058 | City contributions must be sufficient so fund is 90% funded by end of FY2058 |

| Relevant Public Act | P.A. 99-506 | P.A. 99-506 | P.A. 100-23 | P.A. 100-23 |

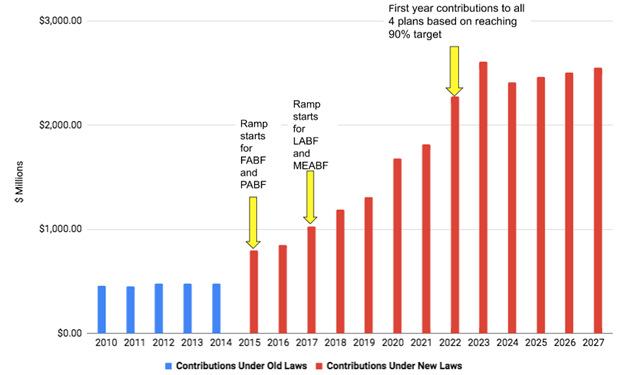

Budget year 2022 was the first year that the City’s contributions to all four systems were based on a funding plan to get each fund to 90% funded rather than fixed dollar amounts—this is what Mayor Lori Lightfoot is referring to when she says Chicago has climbed the pension ramp. The chart below highlights how much the City’s contributions have increased under the new funding laws as compared to the old laws (in blue, years 2010-2014). I also have highlighted when the ramp periods started for the different pension funds. Climbing the pension ramp is an accomplishment, and the City is putting substantially more into the pension funds today than it was a decade ago.

If There’s A Funding Plan in Place Why Are Pensions Still An Issue?

Public Acts 99-506 and 100-23 put in place funding plans that avoided the certain disaster of insolvency. But even though what the City has to pay into the pension funds has been changed and we no longer have the goofy multipliers, challenges remain. The first is that the City has to maintain its contributions at a high level for decades (until the 90% targets are reached). For 2022, the pension contributions were about 14% of the City’s total $16.6 billion budget (p. 36 of the 2023 budget overview). 2022 is a bit of an unusual year because the City still has federal funds from the American Rescue Plan Act.

The pension contributions are likely to account for a non-trivial portion of the total budget for years to come, and because these contributions are required by state law the City doesn’t have discretion over them like it does with other areas of the budget. Adding to the (potential) budgetary pressure is that because the pension funds must be 90% funded by the end of specified years, if their funding levels decrease even further between now and then the City’s required contributions will increase (meaning they’ll be higher than even what’s shown in the above chart).

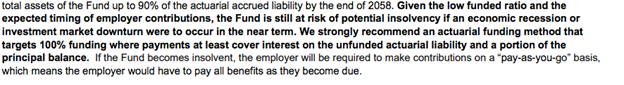

Another issue is the solvency of the pension funds. Chicago’s pension funds are severely underfunded and still at risk for insolvency. Yes, that risk remains even though the City has put billions into the pension funds over the past few years. MEABF’s actuarial firm explicitly warns of this in the 2021 actuarial report as shown in the excerpt below:

(see also this Pensions & Investments article)

Chicago’s low funding levels also ends up eating into the pension funds’ investment performances (remember investments are one of the key sources of assets). This is because in some instances the pension funds have to liquidate assets to maintain benefit payments and cover other expenses.

The City’s contributions are also still below actuarial recommendations. Remember, the funding laws only get the pension funds to 90% funding levels and the best practice is to strive for full funding (meaning a 100% target). Actuaries also recommend paying down unfunded liabilities in a shorter time frame than Chicago’s 30+ year plans. Last, (and this is way too in the weeds for this post) Chicago’s funding plans, by design, backloads contributions (meaning we’re choosing to pay more in the future for lower payments today). For just the MEABF, the amount actuaries recommend the City contribute is about $300 million more than statutorily required contribution for 2022 (see Exhibit IX, on p. 63 valuation report). Now the City’s pension contributions don’t happen in a vacuum, they are part of the overall budget There’s no easy way to increase the City’s contributions beyond current levels–doing that requires A) increasing revenue (through economic growth, new taxes, or higher taxes), B) cutting spending elsewhere in the budget, or C) a combo of both.

I bring these issues up because while yes, Chicago has “climbed the ramp” in terms of its contributions the pension funds remain significantly underfunded and will for years to come AND the City basically has to stay at the peak of this mountain for many, many years.